Common knowledge is not what I know or what you know. Common knowledge is what everyone knows that everyone else also knows.

A simple concept that is central not just to game theory but to the financial markets too. Without the concept of common knowledge, it is difficult to explain why markets are the way they are.

Most investors are aware of this, even if they do not use this explicitly in their decision making. Observe how everyone agrees that Asian Paints is a high-quality business that deserves to trade at a premium to other stocks. Since everyone is aware of this, the price of the stock does not fall too much even in a market meltdown. Common knowledge can work as a self-fulfilling prophecy for a long time.

However, what most investors aren’t aware of is that common knowledge is built up covertly, never explicitly. It is only after a tipping point is reached that it becomes common knowledge. Look at the same stock again, Asian Paints was known as a good stock even in the 2003-08 run but it attained cult like status only after 2015.

In the macroeconomic context, the omnipotence of central banks is a good example of common knowledge. Everyone knows that central banks step in with QE and other liquidity measures when a crisis hits the financial markets. This wasn’t common knowledge till 2008, it is only after the media popularized the term “Bernanke Put” that the omnipotence of central banks was accepted as common knowledge.

Low interest rates post the GFC in 2008 is another theme that became common knowledge over a period of time. The market was worried about inflation for some time post QE3, it is only after PIMCO popularized the term “the new normal” that every market participant accepted that interest rates were likely to stay low in the developed markets.

To make things very simple, common knowledge is nothing but the dominant narrative of the time.

Going back to a few episodes in history

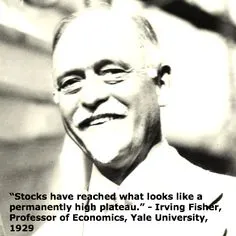

- Before the stock market crash of the great depression broke, almost every participant believed that stocks would stay at elevated levels for a long time. Read the headlines before the market crash to get a sense of how things were.

- The NIFTY FIFTY crash of the 1970’s in the US was preceded by a similar narrative that the best companies in the US would always make for the best investment. No price was too high for a consensus good business then.

What happened next was this…

- Investors during the dotcom boom believed the narrative that valuation and profits were irrelevant for the new age businesses that could grow at very high rates for decades to come.

- Before the GFC hit in 2007, credit markets believed that housing prices in the US would never crash. Complex derivatives were priced and packaged with this underlying assumption that the risk of mortgage defaults would be very low.

Enough history, time to come back to the present.

It should be rather obvious that the biggest fragilities in the market are embedded in the dominant narratives of the day. What really breaks the market’s back is something that the market takes for granted, but turns out that it isn’t so.

Some dominant narratives today

- The Indian market is always a buy over the long term

- A few high-quality businesses have always traded at premium valuations and will always trade at elevated valuations. Valuation is irrelevant for these chosen few

- Private sector banks always make for better investments compared to PSU banks

- There will rarely be a secular growth trend in infrastructure, capital goods, power, farming and other economy facing sectors

- SIP is the best way of investing in the equity market. Also, mutual funds sahi hai

- RBI will always prioritize the interest of savers when it comes to setting interest rates

- Things will mostly work out well over a 5-year period for stock investors

Investors should objectively evaluate each one of these and come to their own conclusions. Every once in a while, wear your most pessimistic hat and think about the dominant narratives of the time and what could happen if any of the them unravels. The key is to think like a pessimistic every once in a while, however do not act like one.

One should always track the narrative and not just the earnings on stocks too. Some stocks have good earnings but no narrative, they struggle to trade at a premium even if numbers continue to support. While some other stocks have not just numbers but also have a narrative that is popular. Investors should take into account the narrative too, for so long as the narrative stays the price can stay irrational. Once the narrative breaks, things can go South pretty quick.

Investing is a full-time job for good reasons.

The more you probe, the more you discover how many different layers exist and how superficial your thought process is.

Simplicity makes for a good sales pitch but doesn’t necessarily work as the best lens when making investing decisions.